A very respected ex-CFO friend of mine forwards a lot of interesting articles to read. Right after Christmas one year, this story appeared in my e-mail, with the headline, “Bernie Madoff Sent A Letter To CNBC On Christmas Eve.”

Now, I have a great respect for my friend. He’s smart, wealthy, knows a lot of the right people, a loving father, all the rest.

But, Bernie Madoff? Recommending I read a letter from the money manager and a former chairman of Nasdaq who ran a Ponzi scheme that defrauded people of $50 billion? What could possibly interest me from a man like that? More important, is anything this guy has to say reliable?

I popped the link, which contained the full text of his letter, which starts like this: “A number of you have been asking my views on a couple of subjects that I am comfortable in going on the record, because they are not related to my case.” I stopped reading and asked myself, “Who would ask Madoff anything?”

I scanned words like “dark pool” and “hedge funds” and stopped reading, since those are completely out of my area and of no interest. After all, hedge funds are how he defrauded people – isn’t it? I replied to my friend, “Why should anyone care what this guy has to say?”

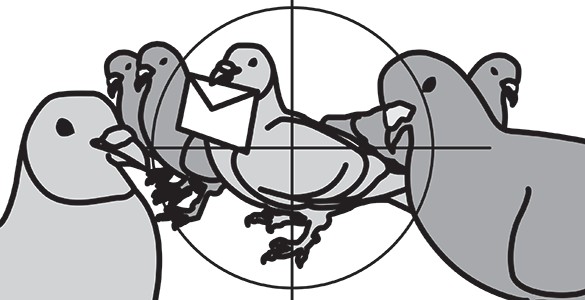

He replied, “Don’t shoot the messenger, if the message is meaningful.”

What is Reliability in Narration?

I guess the question is: What is meaningful? Moreover, if a message isn’t meaningful, then it’s OK to shoot the messenger – right?

People lose reliability – or should lose it – when they lie – and get caught lying1. If you don’t get caught in an unreliable narration, does that mean you are not a liar or that the “readers” haven’t caught you yet? In other words, was Madoff a crook before he got caught? My essay What Does Ethics Really Have to do With Buisiness might interest you.

As a crook, before he got caught, “readers” of Madoff’s stories believed him. Even though he was a liar, they gave meaning to his narrative (otherwise, why would they have invested?). After he got caught, then suddenly ALL of his narrative was put into question. The funny thing is, those narratives didn’t change: they were always delivered by a crook (Madoff). The people blamed Madoff, but they should have blamed themselves.

I remember reading a piece in The Wall Street Journal called, “Why We Keep Falling for Financial Scams” by Stephen Greenspan. Greenspan is a smart guy – an emeritus professor of educational psychology at the University of Connecticut and author of “Annals of Gullibility.” In the article, he admits that, “After I wrote my book, I lost a good chunk of my retirement savings to Mr. Madoff, so I know of what I write on the most personal level.” He uses himself as a case study, “to illustrate how even a well-educated (I’m a college professor) and relatively intelligent person, and an expert on gullibility and financial scams to boot, could fall prey to a hustler such as Mr. Madoff.” I encourage you to read the article, because it’s really about greed – not gullibility. More important, it is about understanding what the reliability of a narrator truly means, and who gives the narrator his reliability.

Are you Gullible or Greedy?

Greenspan calls his “belief” in the Madoff narratives being gullible. It’s not: it’s greed. You see, things in themselves do not have meaning. People give them meaning – or don’t. It’s not the leader that has the power: It’s the followers who give that leader the power (read my blog on Leadership in Today’s Word). It’s the readers (followers) who empower tellers of stories with reliability. People blame Madoff for robbing them when, in fact, they allowed themselves to be robbed because of their own greed. There’s no free lunch.

Understanding that there is no free lunch is called experience – which has to do with trust.

In the study of English literature, you have to “trust” the narrator, which in third person narration, always holds true. The problem is in life there is no third-person narrator: we are all characters IN a story, and we don’t always speak the truth (we try, but that’s another story).

For Greenspan and anyone else who invested in hedge funds run by Madoff, well, buyer beware (remember what P.T. supposedly said – there’s a sucker born every minute). Stories are stories, and after you find out in a story that the narrator is unreliable, you put the book now and say, “What a jerk.” In real life when you put it down, you might lose a fortune. Or a friend.

Messengers (narrators) have an obligation to convey reliable information – or information that sparks thinking. I wanted to share this experience because of my friend’s comment, and because my friend found something in Madoff’s letter that was “meaningful.”

In the original broadcast at CNBC, they end their discussion talking about the relevance of “hearing” from a guy like Madoff. Scott Cohn, the reporter to whom Madoff corresponded, is asked by the announcer, “Why do we care? Does he have any credibility?” Cohn argues that despite all of his crimes, “he was also once a big player on wall street and helped set up a lot of the systems that are in place today with the markets.”

Perhaps that is what my friend meant because the end of Madoff’s letter goes like this: “They (feeder funds) have continued to grow. It has been this additional layer of costs that have created the need for more risk to be taken to earn worthwhile returns. This has created a minefield of regulatory problems involving the very reasons that the desire for a lack of transparency has grown.”

Pardon me? Is this crook calling out a problem with a growing “lack of transparency?” Huh?

You see, while messengers have obligations to convey messages truthfully, receivers of the message have an equal if not greater responsibility: to listen carefully to the message. One of the best ways I have found in judging messages is not just listening to the content, but to ask: why is this person telling me this?

Take this blog: why am I telling you this? What is my motive? Is it pure, or is there something else going on. Am I trying to selling you something?

In a way, yes. I’m selling the art of listening — an increasingly lost art in our world of over-messaging. Even Cohn added, “Obviously you take it all with a grain of salt, but we put it out there for everyone to evaluate…they can make of it what they will.”

What the hell does that mean?

I re-read the letter and stick to my conclusion: there’s nothing Madoff has to offer in ANYTHING he says. He has lost his reliability as a narrator. As I learned very early,“One moment of weakness, and everything is lost. Theory, and practice.” Thank you Albert Camus.

At Interline we have striven to be reliable narrators. Since I started our company in 1990, we have understood – and most of our clients valued – that our narration MUST be reliable to help them succeed. When a client stopped believing us, we lost a client. However, it didn’t mean we lost our inherent reliability.

You see, none of us has the power to force reliability of our narration on others. It is the listeners who judge it.

And we have sought the truth – often telling our clients things they do not want to hear (I remember advising a client NOT to advertise and seeing a stunned look on his face. After all, I am an ad man).

As we enter into another year of difficult business, please keep that in mind for your next project. And if you are looking for reliable narrators, you’ll find them here. Our pillars – service and knowledge – remain unchanged for 30 years. Thanks for reading this.

_________________________________

1I think meaningful narration stems from your reliability as a narrator. When I was in college studying English, we were taught that there are only two ways to narrate a story: in the first person, or in the third person. The third person narrator uses statements like “John was a good boy.” If the story is to be meaningful, you have to believe this narrator. They called this type of narrator the god-like Omniscient narrator. For example, in the story of Job in the Bible, if you don’t believe the first line that Job is a good man, then you won’t understand the story of Job. So you give your belief to the third person narrator and understand “he will never lie to you.” But a story can also be told in the first person – by a character IN the story. The narrator here would say something like “I am a good boy.” If you read the story “I” am telling, then that “I” should “show” you good through actions, but if “I” go around kicking people for no reason, then my reliability as a narrator comes into question. Once the “I” loses reliability as first-person narrator, “I” can never get it back; in other words, no one can believe what “I” say once the reader catches the narrator in the lie, and the entire story comes into question. My meaning, in other words, disappears like smoke.